Professor, Department of Archaeology, Okayama University, Japan.

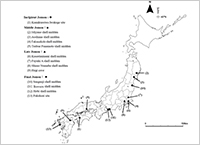

Enlarge Image Map showing spatio-temporal distribution of sites where injured bones from the Jomon period were discovered (Ref. 1).

Enlarge Image Conducting excavation survey of Jomon ruins in Tottori prefecture with students.

Enlarge Image Discussion with students about reports on remains of injured human bones

Enlarge Image

Challenging conventional wisdom on the origins of human warfare.

New research indicates that violence and warfare were not common in prehistoric Japan during the Jomon period 16,500 years ago (14,000 – 800 BC). These findings contradict archeological based research on society in prehistoric Africa and Europe.

Scientists have been intrigued about origins of human warfare for centuries. Notably, clarification of the origins of human lethal conflict and warfare is important for clarifying human evolution, and possibility for a more peaceful world of the future.

Analysis of skeletal remains in Africa and Europe for lethal injuries likely to have been inflicted in wars suggests that human warfare was widespread in hunter-farmer societies in prehistory. Hence, prominent scientific reports suggest warfare is being an intrinsic part of human nature.

But recently, these findings based on altruism and intergroup conflict have been challenged by new research conducted by Naoko Matsumoto at Okayama University and colleagues in Japan and UK [1]. “Our findings for prehistoric Japan during the Jomon period 16,500 years ago (14,000 – 800 BC) indicate that violence and warfare were not common during this era in Japan,” says Matsumoto. “Our results contradict research based on human remains in Africa and other parts of the world, which suggest widespread warfare amongst prehistoric groups of humans.”

Matsumoto and colleagues analyzed Japanese language catalogs of information on human skeletal remains classified as having died from violence. “Our analysis included datasets on age, sex, discovery site, and the time frame in the Jomon period,” says Matsumoto. “We also plotted spatio-temporal “hot spots” of violence on a map of Japan.”

The analysis revealed that 1.81% out of 2576 skeletal remains had died of violence over the entire Jomon period. “Our finding of only 1.81% mortality due to violence is much less than previous reports of 12-14 %, and no evidence of hot spots,” explains Matsumoto. “Our findings challenge the view that warfare is inherent in human nature.”

Matsumoto and her colleagues are continuing their research, and will be focusing on the Yayoi period in prehistorical Japan dated 800 BC to AD 250.

Reference

- H. Nakao, K. Tamura, Y. Arimatsu, T. Nakagawa, N. Matsumoto, T. Matsugi, Violence in the prehistoric period of Japan: the spatio-temporal pattern of skeletal evidence for violence in the Jomon period, Biology Letters 12: 20160028 (2016).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0028

Further information

Naoko Matsumoto website (In Japanese)

http://www.okayama-u.ac.jp/user/arch/about/matsumoto.html